![]()

Maria Madalena, a resident of the Ilha Mercês quilombo (maroon) community

“My parents and grandparents died here. How can Suape call us trespassers?” asks Maria Madalena da Silva, aged 65, a resident of the Ilha Mercês quilombo (maroon) community where 90% of the population live off farming and fishing. She knows the answer. The construction of the Suape Industrial Port Complex, a mega-project covering 13,500 hectares on the south coast of the state of Pernambuco, began in 1978 on lands inhabited for generations by traditional communities.

By law, these residents have the right to stay. However, this is not the case for families that have lived there for over a century. More than 25,000 people lived in the region before the project began, according to data from the Suape Forum, an organization that offers assistance to local quilombo, riverside, fishing, shellfishing, coconut breaking and farming communities. Today, there are fewer than 7,000 and they are all treated like trespassers inside the traditional territory.

What has been responsible for the forced exodus, say the families, is the Governor Eraldo Gueiros Industrial Port Complex, better known as Suape. It is a mixed corporation with an estimated share capital of more than R$1.2 billion and the majority partner is the Pernambuco state government.

![]()

The petrochemical plant installed in the Suape Industrial Port Complex, in Pernambuco. Of the 25,000 people who used to live in the region, more than 18,000 have left

For the municipalities of Ipojuca and Cabo de Santo Agostinho, Suape serves as a port and a business hub, providing infrastructure on large plots for companies interested in expanding on the regional market or increasing their exports. These include Unilever, Fedex, Toyota, Deca, Campari, Pepsico and Solar Coca-Cola. The more than 100 companies installed in the complex exceed R$50 billion in private investments and employ more than 18,000 people, according to the government.

It was under the administration of former governor Eduardo Campos, who was killed in an aircraft accident in 2014, that the complex expanded and acquired the status of the “Engine of the Northeast”. The current governor is Paulo Câmara, the political protégé of Eduardo Campos. In January this year, the then state housing secretary Marcos Baptista took over as chairman of the complex and vice governor Raul Henry was made head of the state economic development department, which is responsible for Suape.

![]()

{ One of the houses demolished in the Ilha Mercês community. The case is being investigated by the Federal Prosecutor’s Office

The benefits publicized by Suape – income generation and employment coupled with environmental preservation – are posted on billboards around the industrial zones. But you don’t have to go far to find the direct impacts that are absent from the marketing of the complex.

Residents who resist tell of serious violations, including threats – sometimes with the use of guns – made by employees of the complex. They also talk about restrictions on access to the land, unauthorized charges and demolitions without warrants – and a number of other complaints. At least three traditional communities have filed complaints against Suape to the Federal Prosecutor’s Office.

“The state of Pernambuco, through the Suape company, is currently the leading violator of human rights in the country,” said Heitor Scalambrini, who has a PhD in energy and is the coordinator of the Suape Forum. Since it violates the UN Sustainable Development Goals, civil society organizations have chosen Suape as a symbolic case in Brazil. In the past, another complaint made it to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

![]()

A sign praises the alleged merits of Suape. More than 100 companies are installed there

A new report by the Getúlio Vargas Foundation that will be published in December cites Suape and Belo Monte as anti-examples of what Brazil should already have learned from the construction of large projects. “In both cases, the communities did not participate in the decision-making and there was no transparency in the resettlement of these populations,” said the lawyer Flavia Scabin, coordinator of the Research Group on Business and Human Rights at the Foundation.

Nearly forty years after its creation, the complex appears to be living up to its name. In the Tupi-Guarani language, Suape means crooked paths.

![]()

Pipelines run through people’s backyards in several communities. The population says it didn’t know the risks

A militia of ‘colonels’

![]()

Otacília Rodrigues da Silva’s house was destroyed by a storm two years ago. She says the security guards from Suape stopped her from building a new one

The memory of Otacília Rodrigues da Silva, who has white hair and a desolate look in her eyes, only fails when it comes to remembering her own age. A resident of the Ilha Mercês quilombo community, she can still hear the sound of the storm that knocked down the walls of her house two years ago. This is not her only trauma. “Suape says I can’t build another house. My greatest fear is dying without having my house back”. In tears, she shows us how she has been able to sleep since then: a 10-milligram pill of the tranquilizer Diazepam per day.

Just like Otacília, other families have also been prevented from rebuilding their own houses or from making renovations by the company’s security guards, which the population calls a militia. A video recorded earlier this year shows a resident pleading with the security guards not to tear down a recently built fence. It didn’t do any good. “They are unspeakably violent,” said Scalambrini, of the Suape Forum.

One neighbor of Divanilda Maria da Silva, aged 45, a resident of the Engenho Tiriri community, confronted Suape and was evicted. Her parents, aware that they had no choice, left before. They are still waiting for compensation to this day. “My mother had a huge plantation. She lost everything. It’s hard to explain. How can someone else understand if I can’t feel my own pain?” Vera Lúcia Melo, aged 48 and a leader of the Engenho Ilha community, entered the People Protection Program after she received threats. “They sent me the message that the people from Suape wanted my head.”

![]()

Vera Lúcia Melo, aged 48, entered the People Protection Program after she received threats from Suape employees

Repórter Brasil had access to 22 police reports filed against Suape. Among the accusations are property damage and threats. The witnesses claim that security guards were working together with employees from the municipal government of Cabo de Santo Agostinho and even with armed military personnel from GATI, a tactical battalion that specializes in high-risk missions. Despite all the complaints, the residents say the number is under-reported because some police officers refuse to make the report – which is illegal.

Romero Correia da Fonseca is inspection supervisor at Suape, but residents say he is the head of the militia who controls the security guards. Two companies are responsible for surveillance at the Complex: TKS Segurança and Liserve, which together have 260 men. According to testimonies, Fonseca goes into the communities armed and asks to be called “chief” or “colonel”.

The website of the Pernambuco state Judiciary features at least ten investigations against this employee of Suape. Our reporters contacted the Civil Police, the Military Police and the Army to check his background in these institutions. But the name Fonseca does not appear in any of the databases. In a statement, Suape informed that his job is “only to receive information from the field inspectors.”

Fonseca reports to Sebastião Pereira Lima, the Land and Property Management Officer at Suape. Although he is also called “colonel” – even on the website of the Pernambuco State Legislature – Lima is a second lieutenant in the Army, four ranks below colonel. Our reporters requested information from the Army on the background of the Suape officer. However, it told us that the information cannot be disclosed under the Freedom of Information Law. The request was refused. We have appealed the denial.

![]()

Repórter Brasil had access to 22 police reports filed against Suape. The photo shows the port area of the Complex that covers 13,500 hectares

In a statement, Suape said that it condemns “the use of violence against the native families in the region”, that its employees do not carry weapons when they are working and that the demolitions only occur after agreements are approved in court.

Liserve is also named in one of the police reports. The company is run by the businessman Agostinho Rocha Gomes, a board member of the Business Leaders Group (LIDE) founded by the mayor of São Paulo, João Dória.

By email, the lawyer for Liserve, Emmanuel Correia, denied the charges against the company and informed that the work of Liserve’s employees is to supervise the 170 guards of TKS Segurança.

The Suape Complex, however, informed that the employees of Liserve do indeed inspect the territory, in addition to supervising the security guards. Later on, by telephone, the Liserve lawyer admitted that the employees photograph the houses of “trespassers” or those of residents who put extensions on their houses. Correia said that the guards never get involved in problems with residents, that he was unaware of the accusations and that he would look into the cases. When contacted again, he did not reply before the publication of this article.

The civil inquiry opened by the State Public Prosecutor’s Office to determine the existence of a militia in the Complex was shelved by the prosecutor Janaína do Sacramento Bezerra. Our reporters attempted to contact the Prosecutor’s Office on several occasions up until the time of publication, but were not successful. In a statement, the communication office of the Civil Police denied the accusations and refused to comment on the involvement of GATI in the operations. It said that besides the investigation by DECCOT (Bureau for Combating Crimes Against the Tax Order), another one is underway on the alleged Suape militia. The municipal government of Cabo Santo Agostinho did not respond until the publication of this article.

Quilombo under threat

![]()

Residents of Ilha Mercês recovered memories of the community to obtain federal recognition as a quilombo community

“I may not be able to read, but I know how to speak,” said Maria Madalena da Silva, a 65-year-old shellfisher and farmer. There is no serenity in the blue eyes of the sexagenarian who said she was brought up working from an early age and with sackcloth for clothes. Just like other areas around the complex, the community where Silva was born and raised is also the subject of a dispute with Suape. And like so many communities scattered around the country, Ilha Mercês recovered its forgotten identity in search of protection.

Thanks to the matriarch’s memories, residents came together and restored fragments of the community’s history: a pestle used to grind coffee, the flour mill of a former resident, an old abandoned slave quarters, the birth certificate of a freed slave and the baobab, a large tree native to Africa around which people would celebrate. In October 2016, the Palmares Cultural Foundation, which reports to the Brazilian Ministry of Culture, officially recognized the area as the Ilha Mercês Quilombo Community.

![]()

In the Ilha Mercês quilombo, residents subsist on fishing and farming

In theory, the federal recognition should protect the community from encroachment by Suape, but this is not what has happened. In September 2017, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office and the Federal Public Defender’s Office recommended to Suape that it suspend its intrusions into the community without the consent of the residents, its attempts to purchase land, its bans on the renovation of houses and its unauthorized charges. None of the recommendations were followed.

The Rota do Atlântico Concessionaire, for example, the company that manages the roads leading to the quilombo, still charges tolls from some residents who should all be exempt from this charge. “Anyone who resists the company is made to pay the toll,” said Silva’s son, José Reis da Silva, aged 45 and a leader of the quilombo. When asked, the company said that it fully complies with the conditions established by the Pernambuco state government.

![]()

Babobá, a large tree native to Africa around which people would celebrate.

Suape informed that “it is engaged in dialogue with the authorities involved in order to adjust its provisions to the reality of the region”.

Eminent risk

![]()

Joana Silva, a resident of the Serraria community

The memories of the land where the quinquagenarian Mario Francisco Silva was born and raised, like his great-grandfather, are under threat. A rickety barbed wire fence separates the Massangana community, home to farmers and extractivists, from a thermal power plant run by Energética Suape II S/A, one of the companies installed inside the Complex.

“One of the walls of my house collapsed and when we asked for help, they told us to contact Suape,” said Silva incredulously. Just like in the other houses in the community, the cracks in the walls, he explained, are caused by the operation of the thermal power plant. “When all the turbines are turned on, it feels like the house is going to fall down.”

There is also no shortage of medical reports of respiratory problems, allergies, fainting and lack of appetite – all caused by the gases that are expelled from smokestacks, say the residents. Installed 10 kilometers from the tourist destination of Porto de Galinhas, Suape II is the largest oil-fired thermal power plant in Brazil and its gas emissions contribute to the greenhouse effect.

The bad smell reaches the communities neighboring the plant, such as Serraria. The 22-year-old daughter of Francine Maria dos Santos Silva gives the warning: “Mom, I can smell gas in the yard”. It also leaves a bad taste in the back of your throat.

By email, Suzana Wolf Jordão de Barros, of the legal department of Suape Energia, told us that “properties occupied by a single family in the area around the project are the responsibility” of Suape.

In practice, say the residents, the companies installed in the Complex exempt themselves from any co-responsibility for the environmental and social impacts. Our reporters visited four houses in the community of Massangana. Disregarding the way of life of the traditional populations, where families live on adjoining land, is not exclusive to the thermal power plant. Suape does the same thing, say the residents.

![]()

In the community where Francine Maria dos Santos Silva lives, Suape and the municipal government closed the school without consulting the residents

To undermine the resistance of the communities, the Suape Forum lawyer Luisa Duque said community leaders are now being criminalized. Melo, from Engenho Ilha, is one of them. This year, she was accused of subdividing land and selling plots where she lives. She denies it. The investigation against Melo and other leaders is being conducted by DECCOT. The same thing happened in Massangana.

When contacted, the state government, through its press relations agency, denied the interview request, since it said Suape had already sent a statement with clarifications. The statement [available here in full], however, did not answer the questions.

Survival is harder

![]()

The complaints against Suape made it to the UN this year

“Before, I used to catch 40 crabs in an hour’s work. These days, it takes me all day to catch five or six. The only reason we don’t go hungry is because we help each other out,” said the shellfisher Divanilda Maria da Silva about the environmental impacts that have affected life in the communities.

In the Ilha Mercês quilombo, the mangroves have rust colored stains and fruit trees have died – the result, say residents, of a project in the Port of Suape. Making it harder to survive on the land, said Magno Manuel de Araújo, a quilombo leader, is another strategy of Suape. “They (Suape) shut off the river and sea so we die of hunger.”

The lawyer Caio Borges, from the human rights organization Conectas, also visited the Complex recently. I heard a number of questions from the residents that have still not been answered. “Where does the sewage go from all the companies installed here?” and “How much diesel contamination is there in the sea from the ships in the port?” are two of them. The environmental impact studies that have been conducted are clearly flawed, said Borges, and there are no studies on the cumulative impacts.

![]()

Plate reveals what reaches the mangrove, effluents (liquid waste or sewage discharged into a river or the sea)

The Pernambuco State Environment Agency, responsible for environmental licensing, issued 26 notices of infraction against the Suape Complex between 2010 and 2014 for environmental irregularities – 17 were fines. Between 2008 and 2010, the federal environmental watchdog Ibama applied fines totaling nearly R$2 million, according to a statement from the institution. Of this amount, R$105,000 has been paid and the rest “is under administrative analysis”.

The director of the agency, Walber Santana, played down his ability to ensure that the complex observes environmental regulations. Since 2011, he said, the state agency has required offsetting measures from Suape for an area of 1,075 hectares and the creation of two conservation units. Asked about the impacts observed by the reporters, Santana said officials from the agency monitor the region frequently and residents can file complaints with the Ombudsman’s Office. Although he promised to send us documentation, Santana did not send any until the time of publication.

In a statement, Suape said that “investments [in environmental policies] are in line with an environmental and social sustainability policy in place in the region” and that the “Ecological Preservation Zone occupies 59% of the territory”.

From island to asphalt

![]()

Fishermen who lived on Tatuoca Island were transferred to a housing project far from the sea

The expansion of Suape that had the most impact on local fishing communities was the deepening of the channel at the port, the construction of the Promar and Atlântico Sul shipyards and the siltation of Tatuoca Island. More than 80 families were removed from the island to make way for progress – those who refused were evicted. These residents, who made a living fishing and farming, currently live far from the sea and they have no land to farm in Vila Nova Tatuoca, a housing project built by the federal government’s Minha Casa, Minha Vida (My House, My Life) social housing program. There aren’t even any trees in the streets. They accuse Suape and the company Diagonal − Transformação de Territórios, which was contracted to handle the resettlement, of lying or omitting information.

One of the promises was that every resident would receive the deed for their new house within two weeks. But this wasn’t what they received. Edson Antônio da Silva, aged 45, said employees from Diagonal and from Suape tried to mislead them with a right of use contract proposed by Suape. His uncle signed the document with his thumbprint. In practice, the contract states that the resident has a license from Suape to use the house without making any improvements to the residency, while it also permits the company to make internal inspections without authorization.

![]()

International organizations, such as Conectas, say that Suape did not take the way of life of the traditional communities into consideration

In the life of one family, the impact has been immeasurable. One of the matriarchs returned to the island and shortly afterwards committed suicide. “The way of life of these populations was not observed, respected or reestablished. Not even the minimum was done to guarantee their economic and social livelihood,” said Borges, the lawyer from Conectas. From among the eighty or so resettled families, only eight people are employed, said Silva.

In a statement, Suape said it is unaware of any such complaint and that Diagonal-Ceplan “has no authority to make promises on behalf of Suape”. Diagonal, meanwhile, informed that “the company did not make ‘promises’ but instead advised the community, as provided for in the contract.”

![]()

In the rainy season, streets turn into rivers. In the rich neighborhoods, the situation is different

According to Silva, just over a month ago Romero da Fonseca – the employee who likes to be called ‘chief’ or ‘colonel’ – was in Vila Nova Tatuoca to tell them they would be transferred to Vila Claudete, another housing project with 2,675 40-square-meter houses in rows, located in the outskirts of Cabo de Santo Agostinho, the tenth most violent city in the country. “This is why Suape and Diagonal did not give us the deed to the house,” said Silva.

In a statement, Suape informed that it offered the residents the definitive use of the property, which “grants all rights to the resettled families, except the right to sell the property”. Suape did not comment on the other unkept promises.

This year, Suape offered fishermen and women from one of the three existing associations the chance to go back and fish in off-limits areas of the port, as permitted by Brazilian law, provided they accepted a “private fishing license”, which is illegal since only the federal government can issue this permit. “Is it fair to the other fishermen and women? No. But what else can we do to keep from starving?” asked one of the fishermen who accepted the offer. Suape was asked about this, but its statement did not address the issue of the fishing license.

Four institutions – two national and the two international organizations Conectas and Both Ends – denounced Suape and the Dutch company Van Oord, which was contracted to dredge the port, to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Our survey found that Suape violated a series of international rights before, during and after its construction,” said Caio Borges, of Conectas. It is the first time that a company installed in the complex has been held accountable for the damages.

![]()

The Pernambuco state government, which is the majority partner of Suape, built another housing project, with 40-square-meter houses, to accommodate the displaced families. Whole communities resisted the move

In the Netherlands, the complaint also affected the company Atradius Dutch State Business, which had granted more than R$400 million in credit to Van Oord to carry out the construction works. The complaint claims that Van Oord failed by not “engaging in responsible consultations with all the affected families” and by not being transparent about the impact of the works on the communities and the environment. Contacted several times, Van Oord informed that “the parties in this process are engaged in a mediation process that is subject to confidentiality.”

While complaints of violations committed by Suape find their way to the UN, Unesco, the educational arm of the UN, signed a R$1.3 million international technical cooperation agreement with Suape and the state government in 2016. In the agreement, it states that the environmental oversight programs and the inspection activities are systematized. When contacted, Unesco said that the technical support “does not involve any direct action of Unesco in the day-to-day management of Suape”.

If on the one hand the crooked paths of Suape still affect the daily life of nearly 7,000 people, on the other hand, the threats they suffered have united them. Together, they want to show Brazil the invisible marks of progress in Pernambuco and defend the right to live on the lands where their ancestors grew up.

![]()

Suape did not build a retaining wall on the embankment in Nova Tatuoca, say the residents. There is a risk of collapse

Translated by Barney Whiteoak

A matéria The crooked paths of Suape foi publicada primeiro em Repórter Brasil.

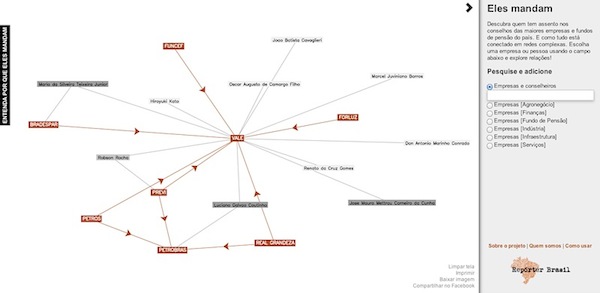

On Wednesday (12/11), Repórter Brasil, a national reference in the defence of human rights, launched Moda Livre (Free Fashion), a free application for smartphones, available for Android and iOS operating systems.

On Wednesday (12/11), Repórter Brasil, a national reference in the defence of human rights, launched Moda Livre (Free Fashion), a free application for smartphones, available for Android and iOS operating systems.