“God allow them to find their lost children,” says one of the websites of foreign missionary groups that work to convert the original groups of Brazil. For them, the “lost children” are the Indigenous people, including the isolated ones. It only takes a few clicks to see that the path to “rescue” them is already outlined, and in detail. A complete mapping of these populations can be found on the websites of these organizations, with various analyses of the “degree of conversion” of each ethnic group, the number of missionary vacancies in the towns where “churches have to be planted” and even a list of those asking for cash donations to carry out these missions.

The work of these evangelists was not interrupted even by the coronavirus pandemic. And, on the last day, on the 21, the missionaries were strengthened in the biblical group of Congress. During the passage of a bill in the House (PL 1142) which provides an emergency plan for Indigenous peoples, deputies linked to the evangelical wing managed to include an article authorizing the permanence of religious missions already in territories occupied by isolated groups. To become law, the bill must be approved by the Senate and sanctioned by President Jair Bolsonaro.

If the COVID-19 crisis strengthened the gaze of religious groups towards Brasilia, in Indigenous lands and in its surroundings, it is no different. “We received information that the missionaries were organizing an expedition during the quarantine,” said Paulo Marubo, coordinator of the Union of Indigenous Peoples of Yavarí Valley (Univaja, for its acronym in Portuguese), to Repórter Brasil. This valley is the region with the highest concentration of isolated Indigenous groups in the country.

“They believe that if they enter [Indigenous lands] in this period, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI, for its acronym in Portuguese) and the Federal Police will not take measures to prevent such actions,” he adds, emphasizing that he considers the work of these missionaries as harassment.

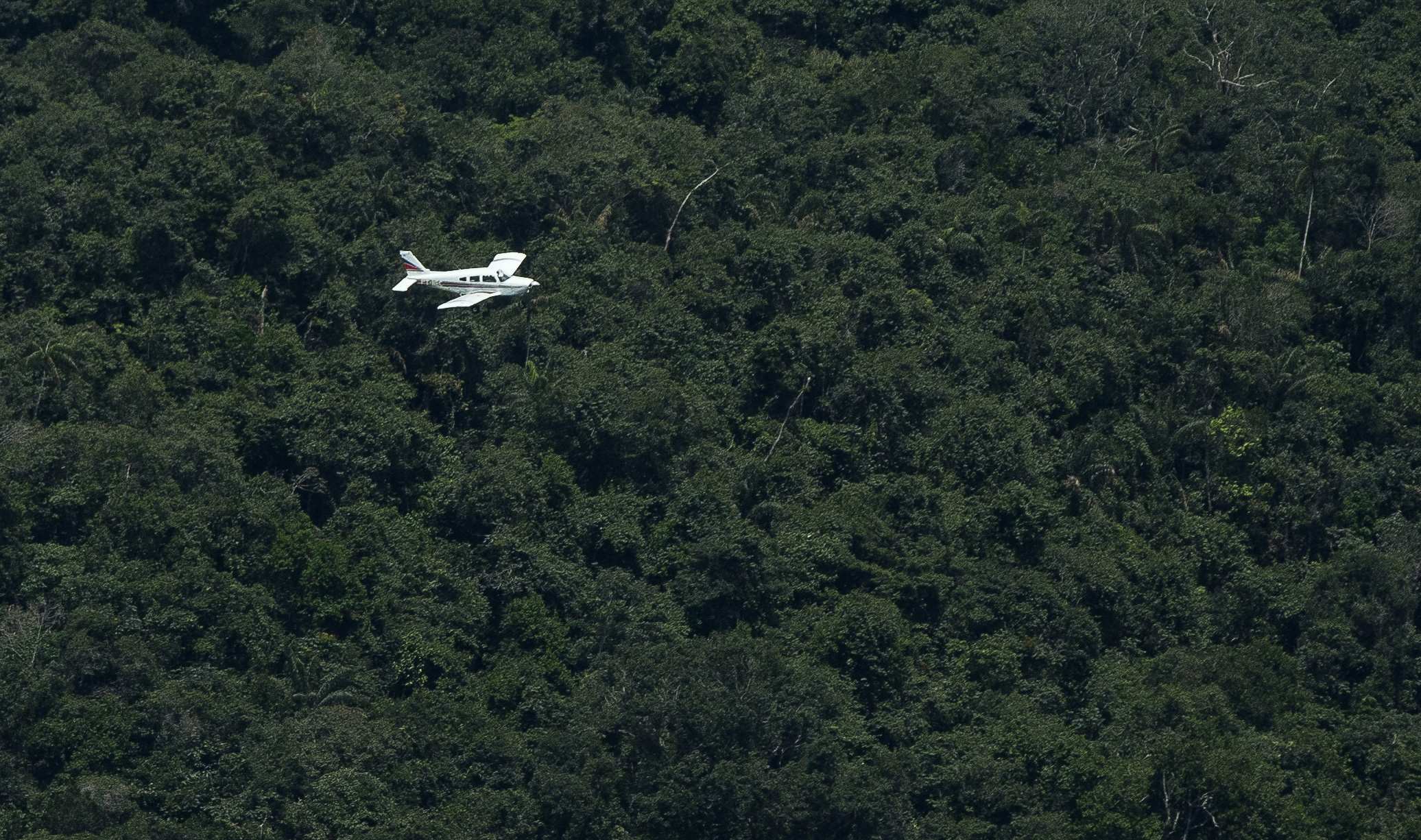

In the Yaraví Valley (AM), the missionaries flew over the territory in a helicopter to contact Indigenous people between March and April. This occurred already in the midst of the pandemic. This was controversial, since at that time FUNAI reported that it had not received a request for authorization to enter towns in the region.

The helicopter was purchased by the New Tribes Mission of Brazil (MNTB, for its acronym in Portuguese), which in January had announced its acquisition for missionary activities. The purchase came after a campaign by Ethnos360 (formerly called the New Tribes Mission), a US missionary organization linked to the New Tribes of Brazil. In a 2018 video, in which it requested donations, the US entity said that the objective was to reach areas with poor accessibility in the extreme west of Brazil, near the border with Peru, the same region where the Yavarí Valley is located. They also asked for prayers for the plane to be used to establish churches “in the isolated villages of this remote region of Brazil.” After being questioned by the newspaper, New Tribes claimed that the helicopter “was purchased with amounts donated by an American businessman who prefers not to identify himself.”

Virtual piggy banks are also often used in order to directly fund evangelists on missions to convert Indigenous peoples. Frontier International, for example, had two American couples working as missionaries at Benjamin Constant (AM). On the organization’s website, there are missionary posts that tell about life in the region and its goals. “Our heart and our mission are to reach those who have not yet been reached among the Indigenous groups of the Yavarí Valley,” says an American couple, in an article that appears just above the link through which they receive donations. Another couple, also asking for donations, comments: “We are going to live on a boat, in the Amazon region, to preach in the villages along the river.”

Vacancies in Brazil

In addition to virtual donations, the websites of these foreign organizations are similar to job search sites. The vacancies are spread across Indigenous groups’ territories around the world, and Brazil appears to be full of “opportunities.” On the Joshua Project website, for example, there are 45 job openings for missionaries who want to plant churches and whose goal is to convert the Indigenous peoples of Brazil. There are even vacancies in the isolated towns of Alto Jutaí and Jandiatuba, both in the Yavarí Valley, and in dozens of other towns, especially in the northern region, such as in the Shanenawa area of Acre.

All the mapped towns are classified with a kind of colored thermometer called a “level of progress”, which marks the conversion rate of a specific group, in addition to other details. The green color shows the towns in Brazil where there is a significant missionary presence (more than 10%) and the red color refers to areas where there is almost no trace of Christianity.

There are also cards to facilitate prayer to reach the people and a link to a video encouraging the missionaries to participate, in which a “hidden tragedy of the Brazilian jungle” is mentioned, since “the opportunity for these tribes to hear the gospel and learn about eternal life is threatened by the increasing restrictions that missionaries suffer when trying to reach them.”

On the website of Finishing the Task, however, vacancies for missionaries who want to “complete the mission” are more restricted. In the most recent map, there are vacancies for two missionaries in Mato Grosso (one in Apiaká and one in Bororo), one in Acre (Katukina-Jutaí), one in Bahía (Tupinambá), one in Pernambuco (Tumbalala) and one in Alagoas (with the Koiupanka group).

By describing each of these ethnic groups, Finishing the Task provides detailed information on how much of the Bible has been translated into a specific Indigenous language, including whether they use the radio and whether there are churches on site. The organization brings together more than 1,500 religious missions “to reach groups that are not yet engaged” and, like the Joshua Project, collects information compiled by other religious associations.

The role of these organizations, mostly foreign, which are mapping the Indigenous groups who will be converted, is fundamental for the missions that operate in Brazil. These missionary groups and whose vice president of Indigenous Affairs is Edward Luz, director of New Tribes and father of the “anthropologist of the rural groups. “ On the AMTB website, the following is stated: “There are several valuable research initiatives that are actively involved in the work of researching who the least evangelized are and where they are.”

A Powerful Ally

These foreign organizations had gained a powerful ally in Brazil. In February, before social isolation, the government of Jair Bolsonaro appointed former missionary Ricardo Lopes Dias, who was already part of New Tribes, to head the FUNAI department responsible for isolated groups. The appointment was criticized by environmentalists, Indigenous organizations and members of civil society and notified to the Federal Prosecutor’s Office (MPF is the Portuguese acronym).

Initially, for the agency, the problem was that Lopes Dias would have access to detailed information on the isolated groups, which could be fed into the already extensive databases of foreign evangelizing organizations.

Later, when COVID-19 arrived in Brazil and FUNAI asked Indigenous people to not leave the villages to avoid contagion, the red traffic light was lit for MPF. He went to court to request the suspension of Dias’s appointment. The MPF argued that Dias’s “omissive conduct” and FUNAI’s “lethargy” in the development of emergency policies for Indigenous peoples in Brazil generated a “concrete threat of genocide with the COVID-19 pandemic, given their low resistance to agents that cause respiratory diseases.”

On the Joshua Project website, for example, there are 45 job openings for missionaries who want to plant churches whose goal is to convert the Indigenous groups of Brazil

The Federal Regional Court (TRF, for the acronym in Portuguese) of the first region accepted the request of the MPF and suspended the appointment of Lopes Dias, on May 21, which was a decision that made the Indigenous leaders feel relieved. However, this Tuesday (9/6), the Superior Court of Justice reversed the TRF’s decision that asked that Dias no longer be appointed to this position.

Other court decisions have also meant defeats for evangelists. In an attempt to avoid contact between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, also due to COVID, the Court of the Amazonas state forbade the entry of missionaries to the Yavarí Valley. In a decision favorable to the lawsuit filed by Unijava, Judge Fabiano Verli, of Tabatinga (AM), mentioned the American pastors Andrew Tonkin and Josiah Mcintyre, the Brazilian Wilson Kannenberg and New Tribes. They rejected all initiatives in this regard and claim to be victims of persecution.

Tonkin, in addition to the accusations of preparing new incursions to contact isolated Korubo ethnic groups in Igarapé Lambança, has already been the subject of two investigations for invasion of other Indigenous lands in the Yavarí Valley, in 2014 and in 2019. The first one was dismissed, but the second one has yet to be completed.

In an email message sent to Repórter Brasil, Tonkin said that he has visited the Amazon region frequently for 13 years, but said that he has been in Iraq since March and therefore could not have participated in the alleged trip to Yavarí Valley. The American declared that he acts as an independent missionary and denied being part of the evangelical Baptist organization Frontier International, despite appearing on several pages of the organization’s website and Facebook page.

When asked about a possible attempt to evangelize isolated groups, he replied: “I only have plans to contact those that the Lord Jesus puts in my way.”

And, ironically, he added: “I did not buy land from FUNAI, I do not plan to build a Coca-Cola factory on any reservation. I’m also not a headhunter of any kind. These are all rumors.”

Repórter Brasil also contacted Josiah Mcintyre, another missionary cited by the decision of the Court of the Amazonas State. But the American declined to comment on the organization’s legacies, saying he has been the target of lies. “God is with me. I leave everything in His hands and He will defend me,” he affirmed.

The third religious individual named, Wilson Kannenberg, works at Asas de Socorro, a Christian missionary organization that provides logistical support, including airplanes, to remote areas. According to the association’s website, they have the “purpose of serving God along with populations with difficult accessibility in the Amazon Region” and they understand that acting in technical manners, such as flying an airplane, is an effective way to reach isolated villages. When looking for him when writing the report, via email and cell phone, Kannenberg did not respond to questions submitted.

Regarding the New Tribes Mission, also cited by the Court of the Amazonas State, it sent the responses by email (read the full text) on behalf of Pastor Edward Luz, denying that they have plans to “contact ethnic groups considered by FUNAI as isolated.”

In Repórter Brasil, FUNAI said that it was not consulted about the entry of missionaries to Indigenous lands in the Yavarí Valley. “Entering the Indigenous territory without authorization is an invasion of the territory of the Union and has legal consequences,” added the foundation. The organization also said that it suspended the granting of new authorizations to enter Indigenous territories and that it has acted in the prevention of COVID-19 with the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health (SESAI, according to the Portuguese acronym) of the Ministry of Health. The entity did not respond to other questions about the role of religious organizations with respect to Indigenous people.

COVID-19, which is rapidly spreading in regions where Brazilian isolated groups live, seems to have emphasized the importance of isolated Indigenous peoples remaining isolated, a policy adopted by FUNAI since the 1980s and which was threatened by the appointment of Lopes Dias.

The coronavirus was the main argument of federal judge Fabiano Verli when he prohibited the entry of missionaries into the Yavarí Valley. “Religious doctrine, although subjectively important to many people, is not, by possible and imaginable constitutional ideology, an essential service,” he wrote in his ruling. “I highlight what I think are good reasons for those who want to spread the beautiful word of Christ to the Indigenous people. But Brazil is a secular state and we have other priorities. Even semi-theocratic and tyrannical states like Saudi Arabia have emptied their temples when faced with COVID.”

O post American religious organizations map indigenous peoples in Brazil and do not disrupt actions with respect to uncontacted tribes, even during the pandemic apareceu primeiro em Repórter Brasil.